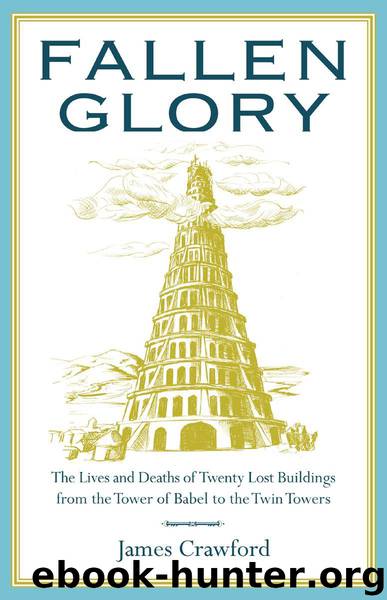

Fallen Glory: The Lives and Deaths of Twenty Lost Buildings from the Tower of Babel to the Twin Towers by James Crawford

Author:James Crawford [Crawford, James]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781908699947

Publisher: Old Street Publishing

Published: 2015-11-03T08:00:00+00:00

On 26 October 1708, Christopher Wren’s son was raised by crane some 365 feet above the streets of London, to place the final stone of the new St Paul’s Cathedral on the lantern at the very summit of the building. The younger Wren, who was also named Christopher, had been born in 1675 – the same year that the foundation stone of the building was laid. The elder Wren had just turned seventy-six. He watched his son ascend the superstructure from the safety of the churchyard below. With this last piece slotted into place, St Paul’s became the first English cathedral to be completed within the lifetime of its original designer.110

Wren’s initial vision for the building had evolved and matured in the years after the Great Fire, but it retained its unifying central device. At last, London’s skyline had its great, classical dome. Clad in radiant copper, it was visible from as far away as the Essex coast to the east, and Windsor to the west.111 That was, of course, on those rare occasions when fog and pollution did not obscure the spectacle. ‘Our air being frequently hazy prevents those distant views,’ bemoaned Wren, ‘except when the sun shines out, after a shower of rain has washed down the clouds of sea-coal smoke that hang over the city from so many thousand fires kindled every morning’.112

The work to replace the gutted shell of Old St Paul’s had been slow, with a number of false starts. In September 1668, Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary of a visit to St Paul’s. Two years had passed since the fire, but in his account, it could have been just two days. He described the ‘hideous sight of the walls of the church ready to fall’ and confessed to being ‘in fear as long as [he] was in it’.113 Apart from clearing the debris from the church floor, almost nothing had been done. ‘It is pretty here to see how the late church was but a case wrought over the old church,’ observed Pepys, ‘for you may see the very old pillars standing whole within the walls of this.’114

Despite Wren’s observations in his 1666 report on the dreadful state of the cathedral’s structure, some of these ‘old pillars’ and piers had survived the disaster and remained so strong that they could only be brought down by a combination of explosives and battering rams. By 1669, thousands of cartloads of debris were being transported down Ludgate Hill and taken away by barge along the Thames.115 ‘Architecture aims at Eternity,’116 Wren wrote in his early thirties. As he removed the last traces of Old St Paul’s to provide a clean slate for his new building, one wonders if he paused to consider the irony of this pronouncement. Picking through the ashes and scarred bones of the old – in the case of St Paul’s, a cycle of destruction and reconstruction going back to Roman times – was surely to come face-to-face with man’s endless capacity for hubris.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Aircraft Design of WWII: A Sketchbook by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation(32277)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31915)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(20487)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19034)

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18612)

Shoot Sexy by Ryan Armbrust(17720)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17401)

Portrait Mastery in Black & White: Learn the Signature Style of a Legendary Photographer by Tim Kelly(16996)

Adobe Camera Raw For Digital Photographers Only by Rob Sheppard(16968)

Photographically Speaking: A Deeper Look at Creating Stronger Images (Eva Spring's Library) by David duChemin(16678)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14634)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14479)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13651)

Art Nude Photography Explained: How to Photograph and Understand Great Art Nude Images by Simon Walden(13029)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11809)

The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon(9058)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8968)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8885)